Constructing the formalism used to deal with symmetries in physics and applying it on the Laplace-Runge-Lenz vector.

Back to homepage https://principiaphysicaegeneralis.com/

Introduction

In physics, every conserved quantity corresponds to a symmetry of the system under consideration. Sometimes the symmetry in question is obvious, like isotropy, but sometimes it is, as the title suggests, hidden. Probably the most famous example of a hidden symmetry is the Laplace-Runge-Lenz (LRL) vector in the Kepler problem. We shall explore the language used in finding and describing the symmetries of a system and then we will attempt to reveal the hidden symmetry that leads to the conservation of the LRL vector.

Symmetry in Classical Mechanics

he language we are going to use to formalise symmetries is that of classical mechanics. Every natural system is described by a quantity called the Lagrangian \(\mathcal{L}\). In most systems the Lagrangian is given by the kinetic energy T minus the potential energy V $$\mathcal{L}=T-V $$ Which gives us the equations of motion through the Euler-Lagrange equations $$\frac{d}{dt} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{q_i}}= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial q_i}\;\;\;(1)$$

Where \(q_i\) is the i-th coordinate and the dot represents the derivative with respect to time.

To get a better grasp on symmetries we need to go a level of a abstraction deeper. To take that step we first need to define the generalised momentum p as follows:

$$p_i=\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{q_i}} \;\;\; (2)$$

Now we use what is called a Legendre transformation to get the so called Hamiltionian of the system \(\mathcal{H}\). To do this we express every \(\dot{q_i}\)

as a function of \(p_i\) through the definition (2), and then we define the Hamiltionian as follows:

$$\mathcal{H} = \sum \dot{q_i} p_i-\mathcal{L} \;\;\; (3) $$

By the definition of the Legendre transformation1 and slight manipulation of (1) using the chain rule, we get Hamilton’s equations of motion

$$\dot{q_i}=\frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial p_i} \;\;,\;\; \dot{p_i}=-\frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial q_i} \;\;\; (4) $$

The first thing we gain by using Hamilton’s approach is reducing a second order differential equation (1) into a pair of first order differential equations (4), but remember our goal is an expression of symmetry. For that purpose we define a quantity called the Poisson bracket.

First, we observe that for any function of p,q ,let’s call it F(q,p) (assuming no explicit time dependency) we can write the time derivative as follows:

$$ \frac{dF}{dt}= \frac{\partial F}{\partial q}\dot{q} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial p} \dot{p} $$

Now, using Hamilton’s equations (4) we get

$$ \frac{dF}{dt}= \frac{\partial F}{\partial q}\frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial p} - \frac{\partial F}{\partial p} \frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial q}= \{F,\mathcal{H}\} $$

As we see the expression of the total time derivative can be compactified using the Poisson bracket symbolism defined bellow

$$ \{A,B\}=\frac{\partial A}{\partial q}\frac{\partial B}{\partial p} - \frac{\partial A}{\partial p} \frac{\partial B}{\partial q}$$

It is important to notice that Poisson Brackets are anti-commutative: \(\{A,B\}=-\{B,A\}\) and that in general \(\{F,G\}\) gives us the rate of change of F under the transformation G. In more formal language, G is called the generator of the transformation defined by the brackets.

And now, we can finally express and explore the symmetries of a system. Let’s say that G is a constant of motion. By definition \(\frac{dG}{dt} = 0 \) which we can now express as

$$\{G, \mathcal{H}\} = 0 =\{\mathcal{H},G\} $$

Notice again that thanks to the anti-commutative nature of the brackets we have gained information as to how G affects the Hamiltionian. In particular we see that the Hamiltonian in invariant or symmetric under the

transformation generated by G. We have now succeeded in connecting a symmetry of a system with a conserved quantity and in particular we have shown that every conserved quantity necessarily corresponds to a symmetry.

To illustrate our new method in action let’s see a simple example.

A Simple Example

The free particle and momentum:

In a simple system, we are going to start with a conserved quantity and find the generated transformation or symmetry of the system. We are going to start with a single free particle in one dimension. The Hamiltionian for this system is just the kinetic energy $$ \mathcal{H}=\frac{p^2}{2m} $$ and it is well known that one of the constants of motion is the momentum p. Indeed, we can easily verify that \(\{\mathcal{H},p\}=0\). Now, to find the transformation we look at how p affects the momentum and the position coordinates of the system through the bracket formalism. In particular $$\frac{dp}{d\epsilon}=\{p,p\}=0 $$ and $$\frac{dx}{d\epsilon}=\{q,p\}=1 $$ where \(\epsilon\) is a parameter used to define the transformation (we can think of it as the strength of the transformation and we expect that for \(\epsilon=0\) the system remains unchanged). Solving the differential equations it is easy to see that the momentum remains unchanged while the position coordinate transforms as follows $$x \longrightarrow x’=x+\epsilon $$ This transformation is a simple displacement of the position of the particle by an amount \(\epsilon\). Therefore, the symmetry that gives rise to the conservation of momentum is the displacement symmetry or the homogeneity of space. In plain words, the fact that the system doesn’t change if we move it by any amount results in the conservation of momentum. More philosophically, we can say that the property of something being the same thing after we move it is momentum.

A More Complicated Example and a Bit of Group Theory

Central Field and Angular Momentum:

For the next example we are going to jump into the real world of three dimensions and assume that our system is permeated by a central potential field. That means that the potential function is only a function of the distance from the center \((V=V(\lvert \vec{r} \rvert))\) so the Hamiltonian is $$ \mathcal{H}=\frac{p_x^2+p_y^2+p_z^2}{2m} - V(\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}) $$ In this case we will be looking at the conservation of angular momentum in this system defined as $$\vec{L}=\vec{r} \times \vec{p} $$ It is now a bit harder to check, but again we have \(\{\lvert \vec{L} \rvert,\mathcal{H} \} = 0\) likewise we have \(\{L_x,\mathcal{H}\}=\{L_y,\mathcal{H}\}=\{L_z,\mathcal{H}\}=0\) so we see that every part of the angular momentum is conserved independently. For simplicity let’s only examine \(L_z=xp_y-yp_x\) by looking again at the effect it has on the coordinates: $$ \frac{dx}{d\epsilon}=\{x,L_z\}=y,\frac{dy}{d\epsilon}=\{y,L_z\}=-x,\frac{dz}{d\epsilon}=\{z,L_z\}=0 $$ Again, solving the equations we get: $$ x \longrightarrow x’=x+\epsilon y ,y \longrightarrow y’=y -\epsilon x $$ In vector notation, the transformation becomes clear $$\vec{r} \longrightarrow \vec{r’} = \vec{r} + \epsilon\hat{z}\times \vec{r} $$ This is the expression for an infinitesimal rotation around the z-axis. We can easily conclude that every component of \(\vec{L}\) corresponds to a rotation around the specific axis. Therefore, the conservation of the angular momentum as a whole corresponds to a rotational symmetry or the isotropy of space.

The Bit of Group Theory:

A group is a collection of elements equiped with a product operation \(\cdot)\) that satisfy certain conditions.

- The product of two elements gives another element of the group (the group is closed)

- There exists an identity e element such that \((e\cdot a)=a\;\; \forall a \in Group\)

We are going to be concerned with continuous groups here, groups with infinite elements, like the group of all rotations (also known as the symmetry group of a sphere, because a sphere remains unchanged under all rotations). In particular the symmetry group of rotations in n dimensions is called \(O(n)\).

Now, a representation (Rep.) of a group is a set of objects paired with a product operation, so that a correspondence can be made between each element of the group and the Rep. and the product relations hold. that means that if

$$a\cdot b = c \;\;\; then\;\;\;Rep(a)Rep(b)=Rep(c) $$

If the correspondence is one to one then we say that the representation is isomorphic. Usually, matrices paired with the matrix product operation are used to represent groups so for example \(O(3)\) can be represented isomorphicaly by the set of all 3x3 matrices with determinant \(\pm 1\)

We are now going to assert without proof that a valid representation of \(O(3)\) is the angular momentum components paired with the Poisson bracket. The characteristic properties we care about are the following relations:

$$ \{L_i,L_j\}=\epsilon_{ijk} L_k \;\;\;(5)$$

Where \(\epsilon_{ijk}\) is the fancifully named fully anti-symmetric tensor of rank 3. By definition \(\epsilon_{ijk} = 0\) if any two indices are the same

and is \(\epsilon_{ijk}=\pm 1\) depending on whether the indices are an even or odd permutation of (1,2,3). Keep these thoughts in mind as we tackle the main event

The Laplace-Runge-Lenz vector

The Kepler Problem

We are going to be concerned with the classical problem of a small mass m orbiting

around a stationary mass M under the influence of Newton’s gravitational law. Our Hamiltonian is now:

$$\mathcal{H}=\frac{p_x^2+p_y^2+p_z^2}{2m} - \frac{k}{\rvert\vec{r}\lvert} $$

Where \(k=GmM\) .We can see that the form of the Hamiltonian falls into the case we explored in the second example. That means that three of the conserved quantities are the 3 components of the angular momentum.

But there is another triplet of quantities (or components of a vector) that are conserved. That vector is the titular Laplace-Runge-Lenz vector (LRL). The definition is:

$$\vec{\mathcal{A}}=\vec{p}\times \vec{L} -mk\hat{r} $$

The solutions to the Kepler problem are ellipses and \(\vec{\mathcal{A}}\) is a vector that is always parallel to the big axis of the ellipse.

This is a strange conserved quantity because there is no obvious symmetry corresponding to it. However, as we now know every conserved quantity generates a symmetry.

To begin our search we are going to find the group that is isomorphic to the total symmetry of the system. To make things easy we will define two new vectors:

$$\vec{M}=\frac{1}{2}(\vec{L} + \vec{\mathcal{A}}),\vec{N}=\frac{1}{2}(\vec{L} - \vec{\mathcal{A}}) $$

Now we observe the following three relations

$$\{M_i,M_j\}=\epsilon_{ijk} M_k\;\;,\;\;\{N_i,N_j\}=\epsilon_{ijk} N_k\;\;,\;\;\{N_i,M_j\}=0 $$

So M and N separately satisfy the same relation as (5) and are “orthogonal” to each other. That means that we have two separate occasions of the group \(O(3)\) which in the language of group theory means that the full symmetry is \(O(3)\times O(3)=O(4)\) where \(O(4)\)

is the symmetry group of a 4-dimensional sphere. Is there then any way of making this symmetry more “visible”? We are going to use an approach first used by Fock on the similar problem of the hydrogen atom.

The Construction:

We now have an idea of what we are looking for. We are looking for a 4-dimensional sphere.

The first fact we are going to use about the Kepler problem , first discovered by Newton himself, is that the path of the momentum vector in momentum space always draws out a circle.

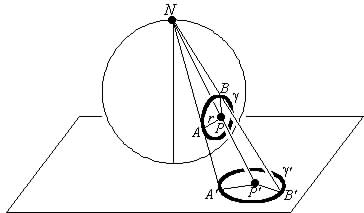

Now we are going to use what is called a stereographic projection of the momentum space onto the surface of the unitary 4d-sphere. Unfortunately we cannot visualise a 4d-sphere but we can look at the 3d equivalent. The important fact for us is that circles in the momentum space are projected into circles on the surface of the 4d-sphere. (Equivalently circles on the 2d-plane are projected into circles on the surface of the 3d-sphere as seen bellow)

If we want to use equations we can use the projection in 4d space suggested by Rogers $$\vec{P}=\frac{2p_o\vec{p}}{p_o^2+\vec{p}^2},P_4=\frac{\vec{p}^2-p_o^2}{p_o^2+\vec{p}^2} $$ Where \(p_o=-\sqrt{2m\mathcal{H}}\) so now we have a circle of radius one with its center at \((0,0,0,0)\) $$\vec{P}^2 + P_4^2 = 1 $$ A similar projection can now be made from the position space onto the 4d-sphere. We have now shown an isomorphism between the Kepler problem and the problem of a particle moving on the surface of a 4d-sphere in the absence of any potential. In other words, every orbit of the Kepler problem can be uniquely mapped onto an orbit of a particle restricted to the surface of a 4d-sphere.

The Interpretation:

In three dimensions there are three parts to the angular momentum, one for each orthogonal axis of rotation. The use of axes (plural of axis) can only be done in three dimensions. A more dimensionaly universal approach is the use of planes of rotation.

Now every part of the angular momentum corresponds to a plane of rotation (\(L_z\longrightarrow x-y\;plane\) etc.). In four dimensions we have six planes of rotation (\(x-y,x-z,x-w,y-z,y-w,z-w\)) so we expect six quantities conserved. In our isomorphism three of the quantities are the \(\vec{L}\) components and the other three turn out to be the LRL vector components.

This is fine and all but someone might rightly think that this process can be carried out for any system where orbits are closed, so what is so special about the Kepler problem? Well, to answer that concern we turn to Russel’s theorem which claims that there are only two types of forces that lead to closed orbits.

One of them is the inverse square one we are dealing with here and the other is that of the harmonic oscillator \((\vec{F}=-k\vec{r})\), no other force (or potential) can create closed orbits. As a matter of fact a similar conserved quantity exists in the harmonic oscillator problem.

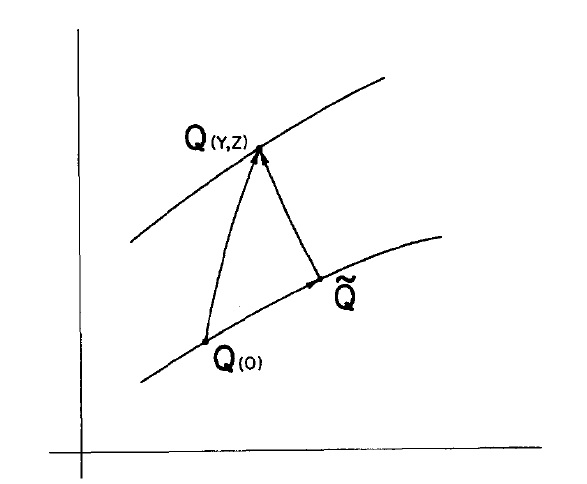

The last thing left to do is, like in our two examples, find the transformation generated by the LRL vector. Rogers does this using quaternions, the most natural language for describing rotations in four dimensions. We are not going to go into the details, but the result on the circles on the 4d-sphere is a projection of the circle onto itself followed by a rigid rotation of the whole orbit (Here, Q is the projected position space not the momentum space).

Again, this kind of transformation projects orbits onto themselves only if those orbits are circles, verifying our interpretation.

Again, this kind of transformation projects orbits onto themselves only if those orbits are circles, verifying our interpretation.

Conclusion and (Re)sources

We have constructed the language of symmetry and we have used the derived formalism to connect conserved quantities with transformations that leave the system (the equations of motion) unchanged. We have also found a seemingly random conserved quantity and managed to link it to a “hidden” symmetry. Now, remember that Fock originally used the 4d-sphere approach to link the hydrogen problem with the \(O(4)\) symmetry2

so this approach is not limited to the classical or “old” world. On the same note, Noether’s theorem, which was the first one to link symmetry to conserved quantities was referring to fields and not particles and the latest theories of fundamental physics also start with the assumption of certain symmetries (gauge field theories).

Back to homepage https://principiaphysicaegeneralis.com/

Sources and Further Reading

- For the classical mechanics basics any textbook is good but I would suggest Arnold’s “Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics” for a more mathematical formal approach or Landau’s “Mechanics” for a more fundamental “physical” approach. Continuous groups and their relation to Poisson Brackets are also dealt with in Arnold’s book.

- The main source of the method used in the LRL vector analysis is Roger’s article “Symmetry transformations of the classical Kepler problem,1972”

- Some historical elements on the Kepler problem and a more dumped down version of Roger’s article can be found in Alemi’s “Laplace-Runge-Lenz Vector, 2009”

- I would suggest reading Fock’s original article on the hydrogen problem but unfortunately (for me at least) it’s in German. “On the theory of the hydrogen atom (Zur Theorie des Wasserstoffatoms)”